不孕不育已成为一个全球性的社会问题,影响着全世界约10% 的育龄夫妇,其中男性不育约占 50%。

对致病基因进行检测,可明确男性不育病因,有助于治疗药物选择,预测睾丸外科取精成功概率以及判断辅助生殖技术治疗预后,并为患者提供遗传学咨询。

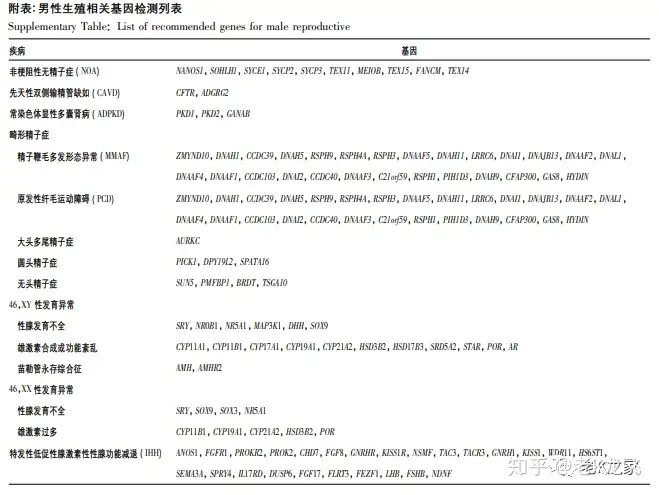

为了规范男性生殖相关基因检测临床应用,中华医学会男科学分会组织本领域专家对相关基因检测适应证、检测方法、检测内容和检测意义等方面进行归纳总结,并结合我国的具体临床实践形成共识。

1、非梗阻性无精子症和重度少精子症

非梗阻性无精子症 (NOA) 和重度少精子症约占男性不育患者总数 的 10% ~ 20% 。其中,染色体核型异常和 Y 染色体微缺失可解释 15% ~ 20% 的NOA及重度少精子 症[7]。除此之外,近年来已有较多研究证实多个单基因变异可导致 NOA。

1. 1 Y 染色体微缺失

1. 1. 1 概述

Y 染色体长臂上存在着控制睾丸发育、精子发生及维持的区域,称为无精子症因子 (AZF) [8],该区域易发生同源重 组,从而导致缺失或重复,引起少精子症或无精子 症。AZF微缺失可解释 7. 8% 的 NOA 和重度少精子症[9]。根据缺失模 式,AZF主要划分为AZFa、AZFbAZFc 三个区域。最常见的缺失类型为 AZFc b2 /b4 亚型,占 6.32%[9]。

1. 1. 2 临床意义

AZFa 区完全缺失导致唯支持细胞综合征(SCOS) ; AZFb 区以及 AZFbc 区完全缺失会导致 SCOS 或者精子成 熟阻滞(MA) [10]。以上两类患者通过手术获得精子的概率几乎为零[10]。AZFa、 AZFb 区部分缺失类型可保留基因全部或部分编码区,有可能正常产生精子[11]。AZFc 区缺失患者临床表现异质性高,50% 的 NOA 患者可通过睾丸手术 取精获得精子。AZFc 区缺失将遗传至男性后代,缺 失区域可进一步扩大。AZFc 缺失患者的精子数目有进行性下降的趋势,应及早生育或冷冻保存精子。

1. 1. 3 检测方法

对于精子浓度少于 5 × 106 /ml 的患者,推荐进行 Y 染色体微缺失检测。Y 染色体微缺失检测推荐以下 6 个基础位点检测: sY84 及 sY86 对应 AZFa 区,sY127 及 sY134 对应 AZFb 区, sY254 及 sY255 对应 AZFc 区。为了区分部分缺失 和完全缺失,建议在 6 个基础位点检测基础上,进行拓展位点检测[10]。

Y 染色体微缺失检测方法包括但不局限于实时荧光定量 PCR 法( qPCR) 、毛细管 电泳法( CE) 、NGS 等。Y 染色体 AZF 区域缺失推荐检测位点主要根据欧美人群建立,是否完全适用于中国人群尚无定 论。鼓励有条件的医疗机构通过高通量检测技术 ( 如 NGS) 进行深入研究。

1. 2 单基因致病变异

1. 2. 1 概述

NOA 和重度少精子症的致病基因主要与精子发生相关。睾丸病理学表型可从 MA 至 SCOS。

1. 2. 2 致病基因

致病基因涉及精子发生的多个生物学过程,包括且不局限于精原细胞增殖及分化 ( 例如 NANOS1、SOHLH1) ,联会复合体形成( 例如 SYCE1、SYCP2、SYCP3、TEX11、MEIOB) ,同 源 重 组 修 复 ( 例 如 TEX15、FANCM ) ,细 胞 间 桥 形 成 ( TEX14) 等,以上基因变异均可造成精子发生障碍。其中,TEX11 变异可解释约 2% 的 NOA 病因[12],其 他基因所占比例尚不明确。

1. 2. 3 检测意义和方法

上述基因变异导致的 NOA 患者,临床上通过手术获得精子的成功率较 低[13]。但临床病例积累尚不足,鼓励有条件的医疗机构进行相关研究,进一步积累变异和病理对应关 系。推荐对 NOA 患者在手术取精前,使用 NGS 对 无精子症相关致病基因进行检测。

2、 梗阻性无精子症

2. 1 先天性输精管缺如

2. 1. 1 概述

先天性输精管缺如(CAVD) 是梗阻性无精子症 的重 要 病 因 之 一,占 不 育 男 性 的 1% ~ 2%[14]。CAVD 分为先天性单侧输精管缺如(CUAVD) 和先天性双侧输精管缺如(CBAVD) 。目前认为 CUAVD 伴肾脏发育不良或缺如和囊性纤维化无关[14]。

2. 1. 2 致病基因

CFTR是囊性纤维化的致病基因。多项中国患者人群研究表明,CFTR 变异可解释 68% ~ 80% 的 CBAVD,以 及 约 46% ~ 67% 的 CUAVD,这部分患者的 CAVD 被认为是囊性纤维 化的轻度表现[16-19]。

2. 1. 3 检测意义和方法

CBAVD 患者和不存在肾脏异常的 CUAVD 患者应筛查 CFTR 基因[20],如存在变异,应继续筛查配偶 CFTR 基因,以判断后代患 囊性纤维化风险。由于中国 CAVD 患者人群不存 在高频率热点变异( 如 F508del) [17,21-24],推荐直接筛查 CFTR 基因全部编码区和 IVS9-5T [25]。

2. 2 常染色体显性多囊肾病

2. 2. 1 概述

常染色体显性遗传性多囊肾病(ADPKD) 的男性患者可出现精囊腺、附睾、前列腺部位等生殖 道囊肿,引起严重少弱精子症、死精子症,甚至梗阻性无精子症,进而导致不育[26]。

2. 2. 2 致病基因

PKD1,PKD2 和 GANAB 基因变 异可引起 ADPKD[27],分别占比 80% ~ 85% ,15% ~ 20% 和 0. 3% 左右。

2. 2. 3 检测意义和方法

PKD1 基因存在 6 个具有极高序列相似性的假基因,需要优化 NGS 捕获探针和 Sanger 测序验证引物,以达到准确检出目的。建议遗传咨询,在生育时建议采取产前诊断或胚胎植入前基因检测(PGT) ,避免疾病遗传给后代。

4 、性发育异常

4. 1 概述

男性性发育异常(DSD) 患者主要以外生殖器男性化不足为特征,可有性腺发育异常,伴或不伴苗勒管结构。根据患者染色体情况,分为 46,XY DSD、46,XX DSD 及性染色体异常导致的 DSD。患者临床表现复杂 多样,例如 46,XY DSD 患者外生殖器可表现为完全女性化到完全男性化[57]。46,XY DSD 发病率约为1 /6 000,根据具体的发病原因分为睾丸发育不良、雄激素合成障碍、雄激素作用异常( 如完全和部分雄激素不敏感综合征) ,其他原因如苗勒管永存综合征和单纯性尿道下裂等。46,XX DSD 根据具体病因分为卵巢发育异常,母亲或胎儿雄激素过量及其他原因( 如苗勒管发育不 良) 导致的性发育异常。性染色体异常主要是由于 47,XXY(克氏综合征及变异型) 、45,X/46,XY 或者 46,XX/46,XY 镶嵌导致的性发育异常[58]。

4. 2 致病基因

DSD 遗传背景复杂,包括多种基因变异[59]。34% ~ 45% 的 DSD 患者可以明确致病基因[60-63]。NR5A1 基因变异是 46,XY DSD 较为常见的病因,约占10% ~ 20%[64]。尿道下裂作为性发育异常的严重临床表现,约 50% 患者能 检出 SRD5A2 或 AR变异[65]。

4. 3 检测意义和方法

不同基因变异导致的性发育异常的治疗方式和预后差异较大,例如,SRD5A2 异常可导致睾酮转化双氢睾酮障碍,可通过雄激素替代、外用双氢睾酮等方式治疗。AR 异常则提示激素替代治疗预后差或无效。推荐使用 NGS 对非染色体异常原因的性发育异常患者进行基因检测以明确病因[58]。

5 、特发性低促性腺激素性性腺功能减退症

5. 1 概述

特发性低促性腺激素性性腺功能减退症(IHH)是由于下丘脑促性腺激素释放激素( GnRH) 合成、 分泌或作用障碍,导致垂体分泌促性腺激素减少,进而引起性腺功能不足的疾病。临床根据患者是否合并嗅觉障碍,将 IHH 分为两类:伴有嗅觉受损者的卡尔曼氏综合征( Kallmann syndrome) 和嗅觉正常的 IHH( nIHH) [66]。

5. 2 致病基因

目前已发现超过 30 个基因可导致 IHH,可解释约 50% 的病例,其中 2.5% 的患者可发现2个或2个以上的基因变异,即存在寡基因致病模式[67]。IHH可伴发其他身体异常,如联带运动 ( ANOS1) 、牙发育不全( FGF8 /FGFR1) 或听力损失 ( CHD7) 等[68],应在临床检查中加以关注,以降低漏检率。中国人群 IHH 患者中常见的基因异常有 PROKR2、CHD7、FGFR1、ANOS1 等[69],推荐优先进行筛查。IHH 新致病基因仍然在不断发现,用于临床诊断时应该评估临床证据是否充分。

5. 3 检测意义和方法

IHH 致病基因遗传模式各有不同,例如ANOS1基因为X染色体隐性遗传,而FGFR1 和PROKR2为常染色体显性遗传。需注意的是,部分常染色体显性遗传的 IHH 基因存在外显率不全,即使变异遗传给后代,也可能不发病或症状较轻微,在遗传咨询时需加以说明。基因检测结果可能用于提示IHH治 疗,例如 GnRH 受体基因GNRHR发生变异,可能预示 GnRH 脉冲治疗预后差;PROKR2 变异患者可能 HCG 治疗预后差[16],但上述证据尚不充分,鼓励有条件的医疗中心进行相关研究。推荐使用 NGS 对 IHH 致病基因进行检测。

6 、基因检测结果对临床管理的影响

基因检测可明确不育症具体病因,以此判断药 物治疗效果、显微取精或辅助生殖技术治疗预后,并 预测后代遗传风险。然而,多数基因变异发生率低, 且有很多变异致病性尚不明确,需不断积累相关基 因诊断和临床数据,以进一步提高基因检测临床使 用价值。

6. 1 减少尝试性治疗

对于原因不明或者特发性男性不育症,患者可能经历多次无效的试验性治疗。基因检测可帮助一部分患者明确病因,从而选择合适的治疗方案。

具体有以下几个方面:

①减少不必 要的药物治疗。例如,DNAH1 基因变异可导致精子尾部畸形率高,药物治疗无效,可建议 ICSI,并有文献证明妊娠结局良好[70];

②判断显微取精手术预后。AZFa 或 AZFb 区完全缺失的 NOA 患者,通过显微取精手术几乎不可能获得精子[10]; TEX11 基因变异可导致减数分裂停滞而引起 NOA[12],通过显微取精手术获得成熟精子概率较低;

③辅助生殖技术治疗预后。由 AURKC 基因变异导致的大头多鞭毛精子,其基因组为多倍体,ICSI 妊娠结局差; 部分 MMAF 相关基因如 DNAH17、CFAP65 等发生变异可能导致 ICSI 预后不良[47],但由于研究病例数较少,证据尚不充分。

6. 2 遗传咨询

部分由于遗传异常导致的男性不育患者可通过促性腺激素或促性腺激素释放激素补 充治疗或替代治疗、显微取精手术等方式成功生育生物学后代,该类患者需重视遗传咨询,防止子代出现相同症状。在明确基因诊断结果和临床意义后,对于符合指征的患者可建议产前诊断或 PGT。

7、 基因检测方法对结果准确性的影响

基因检测技术发展至今,已有多种方法,它们因 其自身优势和劣势,一般存在最佳适用场景。目前在临床基因检测中比较常见的技术主要包括 Sanger 测序、实时定量 PCR、NGS 等。Sanger 测序和实时定量 PCR的适用范围相似,主要应用于单碱基位点变异或者小片段插入缺失的检测,其优势在于准确性高、检测速度快,但缺点是检测通量较低。NGS 的出现弥补了此缺点,极大降低了对多个基因区域同 时进行测序的时间和费用,数据准确性高,已被临床 广泛用于遗传病诊断,同时更快推动了疾病的研究 进展。见表 1。

表 1 常用基因检测技术的比较

Table 1. Comparison of common genetic testing technologies

Sanger测序实时定量 PCR技术NGS适用范围适用于少量位点的检测,可检测已知与未知变异适用于少量位点的检测,只能检测已知变异适用于全基因组检测,可检测已知与未知变异检测通量每个反应只能检测一条序列受限于可用荧光通道数,只能检测少数位点变异高通量检测准确性准确性高准确性高准确性较高检测费用少量位点检测成本较低,但如在单个样本内检测位点较多时,成本极高采用荧光显色法,单位点成本高总体费用较高,但单位点检测成本低临床应用较多用于 NGS 结果的验证主要用于单个基因或少数位点的基因检测主要应用于单基因遗传病的诊断由于男性不育遗传病因学极为复杂,涉及基因较多,且变异大多未经报道,建议使用 NGS 同时对多个相关基因进行检测,推荐使用 NGS panel 对本 共识推荐的致病基因进行变异检测[69,71-72]。

相对 于 全 外 显 子 组 测 序 ( WES) ,NGS panel 具有以下优点:

①仅检测具有明 确临床证据的基因,避免误诊;

②NGS panel 可通过 增加探针覆盖,检测有明确临床意义的非外显子区 域,这些区域在 WES 检测中会被遗漏;

③检测成本 低于 WES 的前提下,NGS panel 可获得更高测序深 度和均一性,从而保证检出敏感性和特异性,有利于 提示镶嵌变异。

需要注意的是,当检测目标基因区域存在特殊性,可能导致检测结果错误或漏检:

①同源假基因的影响。男性生殖相关基因中,相当一部分存在同源假基因,如 ADPKD 致病基因 PKD1,IHH 致病基因 ANOS1,与性发育异常相关的先天性肾上腺皮质增生致病基因 CYP21A2,其假基因同源性大于 90% , 部分外显子区域同源性大于 98% 。

②拷贝数变异影响。拷贝数变异 特别是杂合型、镶嵌型拷贝数缺 失,需优化 NGS panel 探针设计或补充其他检测方法,以避免假阳性或漏检; 当存在某些复杂类型的结构变异时,需优化生物信息学算法,以避免遗漏真实存在的变异导致假阴性。

总之,遗传学检查对于指导男性生殖相关疾病诊疗有重要意义,基因检测指征及处理策略需要在临床中不断完善。随着检测技术飞速发展及更多临床研究的开展,基因检测在男性生殖相关疾病诊断中的应用也将更为深入与规范。

男性生殖相关基因检测专家共识编写组

顾 问

邓春华(中山大学附属第一医院)

谷翊群(国家卫生健康委科学技术研究所)

组 长

商学军(南京大学医学院附属金陵医院)

李 铮(上海市第一人民医院)

孙 斐(南通大学医学院)

编 委

杨晓玉(江苏省人民医院)

史轶超(常州市第二人民医院)

颜宏利(海军军医大学长海医院)

卢慕峻(上海交通大学医学院附属仁济医院)

张峰彬(浙江大学医学院附属妇产科医院)

金晓东(浙江医科大学第一附属医院)

傅 强(山东省立医院)

张志超(北京大学第一医院)

彭 靖(北京大学第一医院)

杜 强(中国医科大学附属盛京医院)

高 勇(中山大学附属第一医院)

刘贵华(中山大学附属第六医院)

王 瑞(郑州大学第一附属医院)

王 涛(华中科技大学同济医学院附属同济医院)

刘 刚(中信湘雅生殖与遗传专科医院)

周 兴(湖南中医药大学第一附属医院)

李和程(西安交通大学医学院第二附属医院)

蒋小辉(四川大学华西第二医院)

安 淼(上海交通大学医学院附属仁济医院)

执 笔

杨晓玉(江苏省人民医院)

刘贵华(中山大学附属第六医院)

安 淼(上海交通大学医学院附属仁济医院)

参考文献

[1] Inhorn MC,Patrizio P. Infertility around the globe: New thinking on gender,reproductive technologies and global movements in the 21st century. Hum Reprod Update,2015,21( 4) : 411-426.

[2] Krausz C,Riera-Escamilla A. Genetics of male infertility. Nature reviews. Urology,2018,15( 6) : 369-384.

[3] Staff A. The Optimal Evaluation of the Infertile Male: AUA Best Practice Statement. 2010.

[4] Hwang K,Smith JF,Coward RM,et al. Evaluation of the azoospermic male: A committee opinion. Fert Steril,2018,109( 5) : 777- 782.

[5] Medicine PCotASfR. Diagnostic evaluation of the infertile male: A committee opinion. Fert Steril,2015,103( 3) : e18-e25.

[6] Salonia A,Bettocchi C,Carvalho J,et al. EAU Guidelines on sexual and reproductive health. European Association of Urology Guidelines,2020.

[7] Tahmasbpour E,Balasubramanian D,Agarwal A. A multi-faceted approach to understanding male infertility: Gene mutations,molecular defects and assisted reproductive techniques ( ART) . J Assist Reprod Genet,2014,31( 9) : 1115-1137.

[8] Vogt PH,Edelmann A,Kirsch S,et al. Human Y chromosome azoospermia factors ( AZF ) mapped to different subregions in Yq11. Hum Mol Genet,1996,5( 7) : 933-943.

[9] 史轶超,崔英霞,魏 莉,等. 不育男性无精子症因子微缺失 的分子与临床特征: 5 年研究回顾. 中华男科学杂志,2010, 16( 4) : 314-319.

[10] Krausz C,Hoefsloot L,Simoni M,et al. EAA/EMQN best practice guidelines for molecular diagnosis of Y-chromosomal microdeletions: State-of-the-art 2013. Andrology,2014,2( 1) : 5-19.

[11] Tang D,Liu W,Li G,et al. Normal fertility with deletion of sY84 and sY86 in AZFa region. Andrology,2020,8( 2) : 332-336.

[12] Yatsenko AN,Georgiadis AP,Ropke A,et al. X-linked TEX11 mutations,meiotic arrest,and azoospermia in infertile men. N Engl J Med,2015,372( 22) : 2097-2107.

[13] Krausz C,Riera-Escamilla A,Moreno-Mendoza D,et al. Genetic dissection of spermatogenic arrest through exome analysis: Clinical implications for the management of azoospermic men. Genetics in Medicine,2020.

[14] Bieth E,Hamdi SM,Mieusset R. Genetics of the congenital absence of the vas deferens. Hum Genet,2020.

[15] Chillon M,Casals T,Mercier B,et al. Mutations in the cystic fibrosis gene in patients with congenital absence of the vas deferens. N Engl J Med,1995,332( 22) : 1475-1480.

[16] Chen Y,Sun T,Niu Y,et al. Correlations Among Genotype and Outcome in Chinese Male Patients With Congenital Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism Under HCG Treatment. J Sex Med,2020, 17( 4) : 645-657.

[17] Yuan P,Liang ZK,Liang H,et al. Expanding the phenotypic and genetic spectrum of Chinese patients with congenital absence of vas deferens bearing CFTR and ADGRG2 alleles. Andrology,2019,7 ( 3) : 329-340.

[18] Ni WH,Jiang L,Fei QJ,et al. The CFTR polymorphisms poly-T, TG-repeats and M470V in Chinese males with congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens. Asian J Androl,2012,14( 5) : 687- 690.

[19] Li H,Wen Q,Li H,et al. Mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator ( CFTR) in Chinese patients with congenital bilateral absence of vas deferens. J Cyst Fibros,2012, 11( 4) : 316-323.

[20] Jungwirth A,Diemer T,Kopa Z,et al,EAU Guidelines on Male Infertility. 2019: EAU Guidelines Office.

[21] Wang H,An M,Liu Y,et al. Genetic diagnosis and sperm retrieval outcomes for Chinese patients with congenital bilateral absence of vas deferens. Andrology,2020.

[22] Ni WH,Jiang L,Fei QJ,et al. The CFTR polymorphisms poly-T, TG-repeats and M470V in Chinese males with congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens. Asian J Androl,2012,14( 5) : 687- 690.

[23] Li H,Wen Q,Li H,et al. Mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator ( CFTR) in Chinese patients with congenital bilateral absence of vas deferens. J Cyst Fibros,2012, 11( 4) : 316-23.

[24] Luo S,Feng J,Zhang Y,et al. Mutation analysis of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene in Chinese congenital absence of vas deferens patients. Gene,2020: 145045.

[25] 赵果果,孙红波,郅慧杰,等. CFTR 基因 5T 位点多态性与先 天性双侧输精管缺如发病风险相关性研究及 meta 分析. 中华 男科学杂志,2019,25( 03) : 231-237.

[26] Torra R,Sarquella J,Calabia J,et al. Prevalence of cysts in seminal tract and abnormal semen parameters in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, 2008,3( 3) : 790-793. [27] Torres VE,Harris PC,Pirson Y. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Lancet,2007,369( 9569) : 1287-1301.

[28] Ford WC. Comments on the release of the 5th edition of the WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen. Asian J Androl,2010,12( 1) : 59-63.

[29] Escalier D,David G. Pathology of the cytoskeleton of the human sperm flagellum: Axonemal and peri-axonemal anomalies. Biol Cell,1984,50( 1) : 37-52.

[30] Ben Khelifa M,Coutton C,Zouari R,et al. Mutations in DNAH1,which encodes an inner arm heavy chain dynein,lead to male infertility from multiple morphological abnormalities of the sperm flagella. Am J Hum Genet,2014,94( 1) : 95-104. [31] Takeuchi K,Kitano M,Ishinaga H,et al. Recent advances in primary ciliary dyskinesia. Auris Nasus Larynx,2016,43( 3) : 229- 236.

[32] Storm van's Gravesande K,Omran H. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: Clinical presentation,diagnosis and genetics. Ann Med,2005,37 ( 6) : 439-449.

[33] Olbrich H,Haffner K,Kispert A,et al. Mutations in DNAH5 cause primary ciliary dyskinesia and randomization of left-right asymmetry. Nat Genet,2002,30( 2) : 143-144.

[34] Coutton C,Escoffier J,Martinez G,et al. Teratozoospermia: spotlight on the main genetic actors in the human. Hum Reprod Update,2015,21( 4) : 455-485.

[35] Tang S,Wang X,Li W,et al. Biallelic Mutations in CFAP43 and CFAP44 Cause Male Infertility with Multiple Morphological Abnormalities of the Sperm Flagella. Am J Hum Genet,2017,100( 6) : 854-864.

[36] Coutton C,Vargas AS,Amiri-Yekta A,et al. Mutations in CFAP43 and CFAP44 cause male infertility and flagellum defects in Trypanosoma and human. Nat Commun,2018,9( 1) : 686.

[37] Baccetti B,Collodel G,Estenoz M,et al. Gene deletions in an infertile man with sperm fibrous sheath dysplasia. Hum Reprod, 2005,20( 10) : 2790-2794.

[38] Merveille AC,Davis EE,Becker-Heck A,et al. CCDC39 is required for assembly of inner dynein arms and the dynein regulatory complex and for normal ciliary motility in humans and dogs. Nat Genet,2011,43( 1) : 72-78. [39] Dong FN,Amiri-Yekta A,Martinez G,et al. Absence of CFAP69 Causes Male Infertility due to Multiple Morphological Abnormalities of the Flagella in Human and Mouse. Am J Hum Genet,2018, 102( 4) : 636-648.

[40] Li W,He X,Yang S,et al. Biallelic mutations of CFAP251 cause sperm flagellar defects and human male infertility. J Hum Genet,2019,64( 1) : 49-54.

[41] Sha YW,Xu X,Mei LB,et al. A homozygous CEP135 mutation is associated with multiple morphological abnormalities of the sperm flagella ( MMAF) . Gene,2017,633: 48-53.

[42] Martinez G,Kherraf ZE,Zouari R,et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies mutations in FSIP2 as a recurrent cause of multiple morphological abnormalities of the sperm flagella. Hum Reprod, 2018,33( 10) : 1973-1984. [43] Coutton C,Martinez G,Kherraf ZE,et al. Bi-allelic Mutations in ARMC2 Lead to Severe Astheno-Teratozoospermia Due to Sperm Flagellum Malformations in Humans and Mice. Am J Hum Genet, 2019,104( 2) : 331-340. [44] Shen Y,Zhang F,Li F,et al. Loss-of-function mutations in QRICH2 cause male infertility with multiple morphological abnormalities of the sperm flagella. Nat Commun,2019,10( 1) : 433.

[45] Sironen A,Shoemark A,Patel M,et al. Sperm defects in primary ciliary dyskinesia and related causes of male infertility. Cell Mol Life Sci,2020,77( 11) : 2029-2048.

[46] Merveille AC,Davis EE,Becker-Heck A,et al. CCDC39 is required for assembly of inner dynein arms and the dynein regulatory complex and for normal ciliary motility in humans and dogs. Nat Genet,2011,43( 1) : 72-78. [47] Touré A,Martinez G,Kherraf ZE,et al. The genetic architecture of morphological abnormalities of the sperm tail. Hum Genet, 2020.

[48] Ray PF,Toure A,Metzler-Guillemain C,et al. Genetic abnormalities leading to qualitative defects of sperm morphology or function. Clin Genet,2017,91( 2) : 217-232.

[49] Fellmeth JE,Ghanaim EM,Schindler K. Characterization of macrozoospermia-associated AURKC mutations in a mammalian meiotic system. Hum Mol Genet,2016,25( 13) : 2698-2711. [50] 李婵娟,张静静,查晓敏,等. 三种畸形精子症的辅助生殖治 疗结局探讨. 中华男科学杂志,2020,26( 8) : 700-707.

[51] Harbuz R,Zouari R,Pierre V,et al. A recurrent deletion of DPY19L2 causes infertility in man by blocking sperm head elongation and acrosome formation. Am J Hum Genet,2011,88 ( 3) : 351-361.

[52] Chemes HE,Puigdomenech ET,Carizza C,et al. Acephalic spermatozoa and abnormal development of the head-neck attachment: A human syndrome of genetic origin. Hum Reprod,1999,14 ( 7) : 1811-1818.

[53] Nie H,Tang Y,Qin W. Beyond Acephalic Spermatozoa: The Complexity of Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection Outcomes. Biomed Res Int,2020,2020: 6279795.

[54] Zhu F,Wang F,Yang X,et al. Biallelic SUN5 Mutations Cause Autosomal-Recessive Acephalic Spermatozoa Syndrome. Am J Hum Genet,2016,99( 6) : 1405.

[55] Li L,Sha Y,Wang X,et al. Whole-exome sequencing identified a homozygous BRDT mutation in a patient with acephalic spermatozoa. Oncotarget,2017,8( 12) : 19914-19922.

[56] Sha YW,Sha YK,Ji ZY,et al. TSGA10 is a novel candidate gene associated with acephalic spermatozoa. Clin Genet,2018,93 ( 4) : 776-783.

[57] Pedace L,Laino L,Preziosi N,et al. Longitudinal hormonal evaluation in a patient with disorder of sexual development,46,XY karyotype and one NR5A1 mutation. Am J Med Genet A,2014, 164a( 11) : 2938-2946.

[58] Cools M,Nordenstrm A,Robeva R,et al. Caring for individuals with a difference of sex development ( DSD) : A Consensus Statement. Nat Rev Endocrinol,2018,14( 7) : 415-429.

[59] Parivesh A,Barseghyan H,Delot E,et al. Translating genomics to the clinical diagnosis of disorders/ differences of sex development. Curr Top Dev Biol,2019,134: 317-375.

[60] Hughes LA,McKay-Bounford K,Webb EA,et al. Next generation sequencing ( NGS) to improve the diagnosis and management of patients with disorders of sex development ( DSD) . Endocr Connect,2019,8( 2) : 100-110. [61] Ozen S,Onay H,Atik T,et al. Rapid Molecular Genetic Diagnosis with Next-Generation Sequencing in 46,XY Disorders of Sex Development Cases: Efficiency and Cost Assessment. Horm Res Paediatr,2017,87( 2) : 81-87.

[62] Eggers S,Sadedin S,van den Bergen JA,et al. Disorders of sex development: Insights from targeted gene sequencing of a large international patient cohort. Genome Biol,2016,17( 1) : 243.

[63] Dong Y,Yi Y,Yao H,et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing identification of mutations in patients with disorders of sex development. BMC Med Genet,2016,17: 23. [64] Wang H,Zhang L,Wang N,et al. Next-generation sequencing reveals genetic landscape in 46,XY disorders of sexual development patients with variable phenotypes. Hum Genet,2018,137 ( 3) : 265-277.

[65] Tahmasbpour E,Balasubramanian D,Agarwal A. A multi-facetedapproach to understanding male infertility: Gene mutations,molecular defects and assisted reproductive techniques ( ART) . J Assist Reprod Genet,2014,31( 9) : 1115-1137.

[66] 中华医学会内分泌学分会性腺学组. 特发性低促性腺激素性 性腺功能减退症诊治专家共识. 中 华 内 科 杂 志,2015,54 ( 8) : 739-744.

[67] Maione L,Dwyer AA,Francou B,et al. GENETICS IN ENDOCRINOLOGY: Genetic counseling for congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and Kallmann syndrome: New challenges in the era of oligogenism and next-generation sequencing. Eur J Endocrinol, 2018,178( 3) : R55-R80.

[68] Topaloglu AK. Update on the Genetics of Idiopathic Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol,2017,9 ( Suppl 2) : 113-122.

[69] Zhou C,Niu Y,Xu H,et al. Mutation profiles and clinical characteristics of Chinese males with isolated hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Fertil Steril,2018,110( 3) : 486-495 e5.

[70] Wambergue C,Zouari R,Fourati Ben Mustapha S,et al. Patients with multiple morphological abnormalities of the sperm flagella due to DNAH1 mutations have a good prognosis following intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Hum Reprod,2016,31( 6) : 1164-1172.

[71] Xu H,Li Z,Wang T,et al. Novel homozygous deletion of segmental KAL1 and entire STS cause Kallmann syndrome and Xlinked ichthyosis in a Chinese family. Andrologia,2015,47 ( 10) : 1160-1165.

[72] Niu Y,Zhou C,Xu H,et al. Novel interstitial deletion in Xp22. 3 in a typical X-linked recessive family with Kallmann syndrome. Andrologia,2018.

本文转自

《中华男科学杂志》

网友评论

最新评论